The Ripple Effect

-News and Commentary-

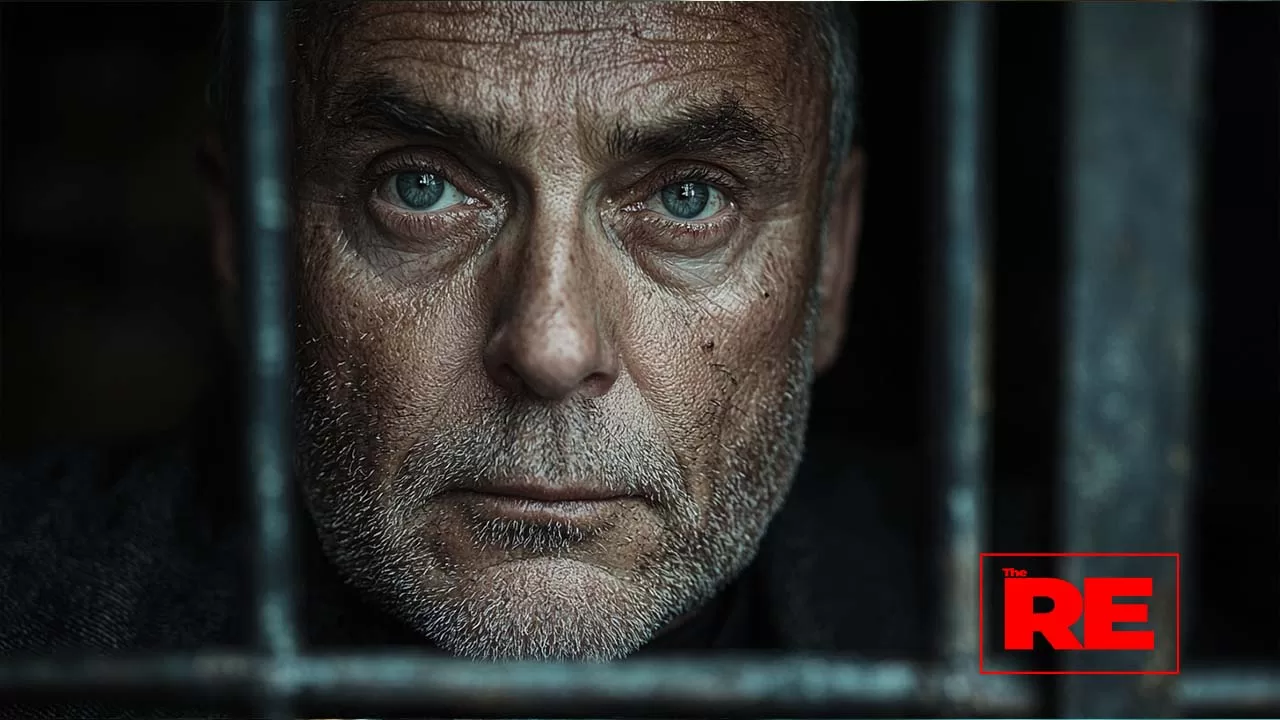

The Hidden Cost of Incarceration: How Prison Labor Still Drives Profit in America

- Home

- News and Commentary

- The Hidden Cost of Incarceration: How Prison Labor Still Drives Profit in America

This is not breaking news. We don't report the news. We Unpack it. Explain it. And analyze what it means.

Click this button to add us to your home screen.

We Unpack. You Decide. Stay informed.

One voice. One message. One Goal. Truth

In America, it’s still legal to force someone to work without pay—as long as they’re in prison. That’s not a metaphor. It’s written directly into the 13th Amendment. Slavery and involuntary servitude were abolished—except as punishment for a crime. That exception has never been corrected, and over the decades, it’s been quietly molded into a system that generates billions. Today, hundreds of thousands of incarcerated people work jobs that look like any other—fields, kitchens, call centers, factories—but for wages that barely exist. Some make cents per hour. Others make nothing at all. The public is told it’s about rehabilitation, but the deeper you look, the clearer it becomes: this is not just a system of discipline. It’s a system of extraction.

Prison labor props up supply chains in nearly every state. Inmates repair roads, clean government offices, fight wildfires, manufacture goods, and even produce products for major corporations through third-party contracts. States save money by using prisoners as workers. Private companies get access to ultra-cheap labor with no benefits, no unions, and no overhead. Refusing to work can result in punishment—loss of privileges, solitary confinement, or denied parole. That kind of leverage turns a sentence into something more than just time. It turns people into a captive workforce. And the longer the system runs, the more it stops resembling justice and starts looking like a business model.

There was a time when I assumed that “doing time” meant isolation, reflection, maybe even accountability. But when you see the logistics of how prison labor operates, it changes the meaning completely. It’s not just about confinement. It’s about production. The system doesn’t just remove people from society—it puts them to work in a way that benefits those on the outside. And the people locked inside it? They’re treated less like individuals and more like inventory. In a country that prides itself on entrepreneurship, it’s not surprising that even incarceration has been turned into an industry. What’s surprising is how normalized it’s become. Somewhere along the line, we stopped asking why. And maybe that silence is what allows it to keep growing.

The prison labor economy does not run on ideology. It runs on contracts, policies, and profit margins. In some states, corrections departments operate like staffing agencies. The difference is the workers do not get to negotiate, switch jobs, or walk away. The system is propped up by a tangled web of legislation and incentives that reward both public and private sectors for keeping incarceration high and costs low. On the surface, these programs are labeled as vocational training or rehabilitation. But look deeper and you will see that many of them have little to do with skill-building and everything to do with sustaining a workforce that cannot say no.

Take the Federal Prison Industries program, known as UNICOR. It is a government-run corporation that employs inmates to manufacture furniture, electronics, textiles, and more, then sells those goods to federal agencies. In 2023, UNICOR brought in over $500 million in revenue. The average inmate worker made less than a dollar an hour. That same model plays out at the state level. In places like Arkansas, prisoners process meat for the state’s agricultural arm. In Florida, they produce uniforms for other incarcerated people. In Washington, inmates have worked in call centers answering unemployment claims during pandemic surges. Every hour worked is an hour that saves an agency money or generates a return for a vendor. These are often under contracts that would be impossible to fulfill at standard labor rates.

For private companies, the benefits are even more pronounced. Through state prison industries or third-party operators, brands can tap into a labor force that is stable, regulated, and extremely low cost. A 2017 report found that at least 4,100 corporations have directly or indirectly profited from prison labor. Some are aware. Some benefit passively through buried contracts in their supply chains. The companies range from small vendors to major global brands. And because the work is often labeled as correctional industries, it avoids many of the wage and safety laws that apply outside prison walls. There are no unions. No job mobility. No sick leave or benefits. The system is designed to ensure labor is always available and always controlled.

The incentives do not stop with companies. Many states rely on inmate labor to balance their own budgets. In Mississippi, inmates must work to gain access to parole, visitation, or other basic rights. In Texas, incarcerated people work full-time jobs without pay while the state avoids millions in staffing costs. Prisons that demonstrate high labor output often receive more funding or support for expansion. That creates a cycle where labor is not just a byproduct of incarceration, it becomes a measure of success. The more productive the prison appears, the more essential it becomes. Once that is the logic, releasing people becomes less profitable than keeping them busy.

There is also the legal structure that supports this cycle. Courts have consistently upheld forced labor in prisons under the 13th Amendment’s exception clause. Lawsuits challenging unsafe or exploitative conditions are often dismissed. In some cases, inmates have been punished for refusing jobs that were dangerous or degrading. Solitary confinement is still used in many states as a consequence for noncompliance. Meanwhile, public interest in the issue stays low. The people affected are not just out of sight, they are locked behind processes most voters never see.

At every level, the design of this economy is meant to operate quietly. Politicians avoid discussing it. Companies outsource the controversy. State agencies manage it like a routine budget line. And the public, for the most part, assumes that if someone is in prison, they probably deserve whatever comes with that sentence. That assumption, that a criminal conviction justifies anything, is what allows the system to keep running. But when you trace the money and remove the excuses, what you see is clear. It is a workforce with no protections, no freedom, and no voice. And that silence is what keeps it profitable.

Talk to someone who has worked a prison job and you will hear the same words over and over: exhaustion, frustration, humiliation. But you will also hear something colder, acceptance. For many incarcerated people, the job is not a stepping stone or a second chance. It is survival. You work because it gets you access to phone time, commissary, or a chance at parole. You work because saying no can cost you a privilege or lock you in a cell for twenty-three hours a day. In some places, you work because there is no other option. Refuse, and you are written up. Refuse again, and it gets worse. What sounds like opportunity on paper quickly becomes coercion in practice.

One former inmate in Louisiana described cleaning prison bathrooms, scrubbing blood off walls and toilets with no protective gear, for thirty cents an hour. Another, who worked in a commercial laundry facility, developed lung issues from prolonged exposure to chemical fumes. Complaints were ignored. Protective equipment was rationed. The justification was always the same. This is prison, not a job site. You do not get to negotiate conditions. You serve your time, and in the process, the system takes everything it can get from you.

When prisoners are injured on the job, they are often denied access to workers’ compensation or outside medical care. Some are disciplined for pretending to be sick or trying to get out of assignments. Others keep going, untreated, just to avoid losing their place on a list or their eligibility for release. That creates a quiet churn of harm. The labor is invisible, the injuries are undocumented, and the long-term impact is written off. Once released, many former inmates carry the damage with them, chronic pain, untreated trauma, and a work history that counts for nothing on the outside.

The mental toll is just as heavy. Incarcerated people are made to work jobs that reinforce their lack of agency. Whether they are manufacturing furniture for state offices, picking vegetables for school lunches, or sewing uniforms they will later be forced to wear, the message is clear. You do not own your time. You do not own your body. And your value is measured by how much you can produce, not by who you are or what you are trying to become. That kind of conditioning does not disappear after release. It lingers. It shows up in job interviews, in relationships, in moments where self-worth is supposed to matter. For many, it never fully goes away.

There are also ripple effects on families. When an incarcerated parent works for pennies, it is not just their time being devalued. It is their ability to support their children, contribute to household stability, or even call home regularly. Phone calls from prison can cost dollars per minute. Commissary prices are inflated. A system that pays people a few dollars a month then charges premium rates for basic needs is not rehabilitating anyone. It is draining whatever support system they have left. And when families cannot afford to keep up, the person inside suffers. The person outside suffers. The pressure spreads.

Even communities feel the impact. Many rural towns rely on prisons for jobs and economic stability. That dependency makes reform harder. A prison with a strong labor program can justify expansion or protect itself from closure. That means fewer incentives to reduce incarceration or improve conditions. In some places, prison labor is seen not as a necessary evil but as a local economic engine. That framing shifts the moral compass. It becomes harder to see inmates as people when their presence fills budget gaps and fuels contracts.

None of this is accidental. It is the result of a system designed to extract value quietly, steadily, and without public resistance. And for the people inside, it is a reminder that time served does not mean time respected. They are not seen as individuals with goals or potential. They are seen as units. Labor units, revenue units, cost-saving units. And when they get out, many face the same obstacles that led them to prison in the first place. But this time, with fewer options and more scars.

The question is not whether prison labor exists. It does. The question is what kind of country normalizes a system that turns punishment into profit while calling it justice. That contradiction is not just a legal loophole. It is a design choice. A country can either build systems that rehabilitate or systems that extract. America chose the latter. It built a model where people are removed from society, stripped of rights, and then placed into roles that serve the very same institutions that benefited from their absence. The courts convict. The prisons contain. The labor is collected. The return on that cycle is not freedom. It is output.

And what makes the cycle hard to challenge is how well it hides behind good intentions. Most prison labor programs are branded as job training. On paper, they offer structure, discipline, or work experience. But the reality on the ground is different. There is no certification. No upward mobility. No career pathway waiting on the outside. The jobs offered inside prisons rarely reflect real-world demand. Instead, they reflect the needs of the system itself—what needs to be cleaned, built, harvested, or packed. And for that, prisoners are told to be grateful. They are told it builds character. That kind of messaging is not just dishonest. It is strategic. Because if enough people believe that prison work is part of redemption, they stop questioning what is actually being redeemed.

What would it take to change this system? Not just reform it at the edges, but actually dismantle the incentive structure that keeps it running? First, it would require confronting the 13th Amendment directly and removing the language that allows forced labor. That change alone would be historic. But even with legal reform, the economic incentives would still remain. States would have to find new ways to fund corrections without relying on unpaid or underpaid labor. Companies would have to rethink their supply chains. And the public would have to shift from a mindset of punishment to one of dignity. That will not happen overnight. But it has to start with clarity.

What is happening in American prisons is not rehabilitation. It is exploitation. And the longer that distinction goes unspoken, the more this system cements itself as just another part of how things work. But it should never be normal for a country to take someone’s freedom and then charge interest on their labor. It should never be acceptable for a human being to risk injury, illness, or mental breakdown for wages that mean nothing outside a commissary slip. And it should never be okay for society to profit quietly from people it chooses not to see.

So what now?

What needs to change? The legal foundation that allows forced labor needs to be rewritten.

Who is responsible? Lawmakers, corporations, voters, and the systems that quietly benefit.

Where does the pressure come from? From the bottom up. From public awareness, from advocacy, from exposure.

When will it change? When silence becomes more uncomfortable than confrontation.

Why does it matter? Because a justice system that commodifies labor is not justice at all.

It is industry. And industry without ethics always looks for the cheapest, quietest way to grow.

This is not breaking news. We don't report the news. We Unpack it. Explain it. And analyze what it means.

Click this button to add us to your home screen.

We Unpack. You Decide. Stay informed.

One voice. One message. One Goal. Truth

and then

and then